Old Testament and Gospels completed in 384 AD

Jerome’s Latin Translation of the Hebrew Masoretic Text

Introduction:

1. About the Vulgate:

a. “VULGATE The Latin translation of the Bible that Jerome produced in AD 383–405 or that was at least initiated by him, with the Old Testament and Gospels certainly being translated by him.” (LBD, Vulgate)

b. “Vulgate. The Latin version of the Bible (editio vulgata) most widely used in the W. It was for the most part the work of St *Jerome, and its original purpose was to end the great differences of text in the *Old Latin MSS circulating in the latter part of the 4th cent. Jerome began his work, at the request of Pope Damasus in 382, with a revision of the Gospels which was completed in 384. Here he seems to have used as the basis of his revision a Greek MS closely akin to the *Codex Sinaiticus. That he revised the remaining books of the NT is unlikely.” (The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Vulgate, 2005 AD)

2. The Need of a Latin Bible: The Latin of the western church at Rome:

a. “The rise of Latin: The sense that Greek was the language of the apostolic books and of the Jewish Scriptures-Christians read and defended the LXX translation as sacred text, not the Hebrew-meant that Latin versions were simply that, versions, and therefore without the same weight as the originals. Nevertheless, as the Latin church grew, so did the demand for Latin translations. By the 4th cent., literally hundreds of copies were circulating, probably in a number of different versions. The North African martyr Felix, a victim of the Great Persecution (d. 303), reportedly refused to hand over the numerous books of the Carthaginian church, despite an imperial decree demanding that he do so, and was therefore beheaded (Acts of Saint Felix). The church of Cirta was less successful, losing most of its library when, in May of 303, thirty-four biblical manuscripts of varying sizes were seized by the proconsul, including one very large manuscript, five large, two small, twenty-five of unspecified size, and one of unbound quinions (McGurk). These early Latin translations, known to Tertullian and Cyprian, possessed by the churches of Carthage and Cirta and employed by the Roman authors such as Victor and Novatian, were informal, however precious they may have been to the churches that held them. As Augustine famously put it, anyone who obtained a Greek manuscript and thought that he had some ability in Greek and Latin went ahead and translated it (Doctr. chr. 2.11.16), a neat explanation for the diversity of the versions known to him at the turn of the 4th cent. Latin-speaking Christians were defining and delimiting their sacred books, and their relationships to them, at the very same time that they were translating them, locally, anonymously, and without a discernible scheme. During the 4th cent., Latin became a focus not only of the Roman imperial administration but of Latin-speaking Christians as well. The emperor Diocletian (r. 284–305) promulgated imperial law solely in Latin, though his capital was in Greek-speaking Asia Minor. Constantine continued this practice, writing speeches in Latin and leaving it to others to translate (Eusebius, Vit. Const. 3.13.1; 4.8). A bilingual law school was founded in Berytus, Syria (modern Beirut), Latin appears with increasing frequency in surviving papyri from Roman Egypt, and significant pagan authors living in Antioch and Alexandria adopted Latin as their literary language of choice (Lafferty). Christians followed suit: Latin was adopted as the principal liturgical language in Rome and Milan, revisions of existing Latin translations were undertaken in earnest, and there was a proliferation of theological writings in Latin by such authors as Hilary of Poitiers (d. ca. 367) and Ambrose of Milan (ca. 339–97). The writings of Origen (ca. 185–254) and other Greek Christian authors began to be carefully translated into Latin by scholars such as Rufinus (ca. 345–411) and Jerome (ca. 345–420). It was in this context that Damasus, bishop of Rome from 366 to 384, likely commissioned Jerome to compose a new translation of the Gospels based on the best Greek manuscripts and yet mindful of ancient Latin Christian traditions. This translation, completed in 383, was designed to produce a version free of the errors of inaccurate translators and copyists (Jerome, Letter to Damasus). Twenty years later, Augustine complimented Jerome for the success of his version, thanking him for producing such a careful translation; he was significantly less enthusiastic about Jerome’s approach to the LXX (see Jerome’s Epist. 71). (The New Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, vol 5, p 765, 2006 AD)

I. Jerome translated the Hebrew MT text into Latin using the lower Chronological numbers:

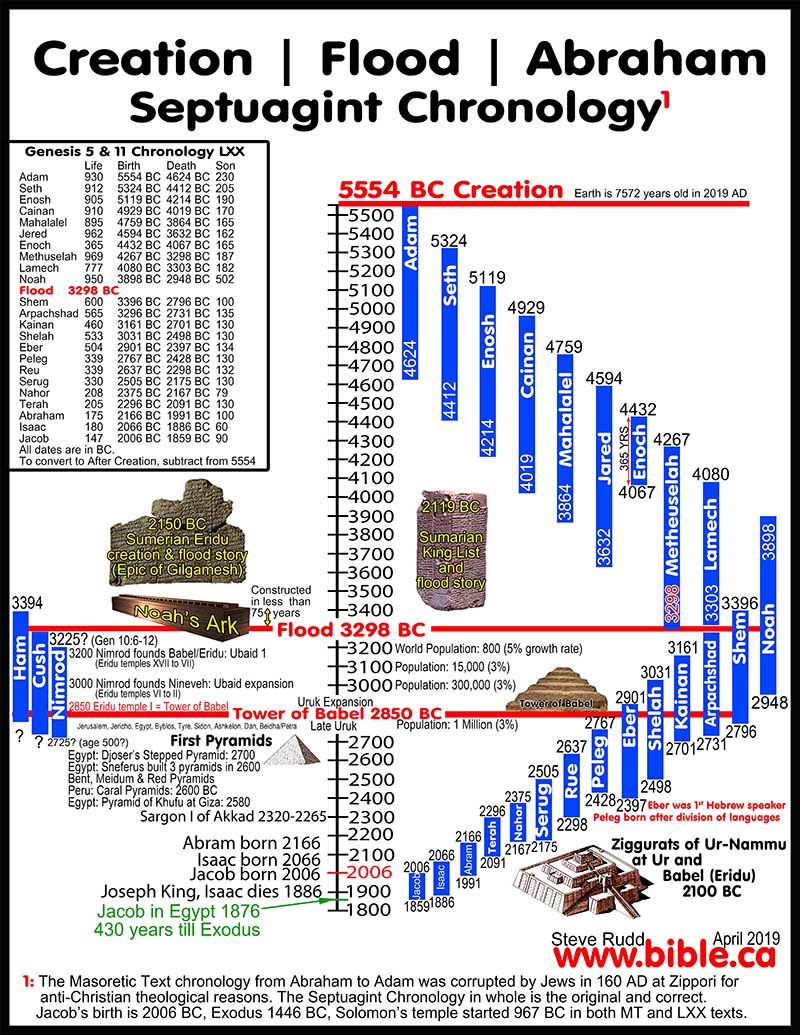

1. Jerome translated the Hebrew manuscript in 400 AD into Latin and followed the lower Masoretic Genealogical numbers in Gen 5,11

a. The Vulgate, which Jerome translated from Hebrew into Latin, supports the 430 year long sojourn.

b. We know that in 400 AD the corruption by the Jews in 160 AD of the Genesis (chapters 5 and 11) chronologies in the Hebrew Masoretic text for anti-Christian purposes was complete.

2. Jerome’s translation of Isa 7:14:

a. There are Dead Sea scrolls that validate the modern Masoretic text translation of Isa 7:14 so Jerome’s translation, like the original Septuagint in 282 BC chose to translate it VIRGIN. After all, if the Jews in 282 BC translated it virgin, it could not be wrong for Jerome to follow the 700 year old Jewish tradition in /

b. Jerome did translate Isa 7:14 as “virgin” in Latin: “propter hoc dabit Dominus ipse vobis signum ecce virgo concipiet et pariet filium et vocabitis nomen eius Emmanuhel” (Isa 7:14 Jerome, Latin Vulgate, 382 AD) “Therefore the Lord himself shall give you a sign. Behold a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son and his name shall be called Emmanuel.” (Isa 7:14 Jerome, Latin Vulgate translated into English)

Conclusion:

1. The Latin Vulgate is an important manuscript because it reflects the Hebrew Masoretic Text of the Old Testament (Tanakh) in 383 AD.

2. It is no surprise then, that the Vulgate faithfully translated the shorter chronological numbers in the Hebrew text that had been corrupted and changed in 160 AD at Zippori.

3. The Vulgate, however, does use the longer sojourn of 430 years of Israel in Egypt.

|

The Septuagint LXX “Scripture Cannot Be Broken” |

|||||

|

Start Here: Master Introduction and Index |

|||||

|

Six Bible Manuscripts |

|||||

|

1446 BC Sinai Text (ST) |

1050 BC Samuel’s Text (SNT) |

623 BC Samaritan (SP) |

458 BC Ezra’s Text (XIV) |

282 BC Septuagint (LXX) |

160 AD Masoretic (MT) |

|

Research Tools |

|||||

|

Steve Rudd, November 2017 AD: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections |

|||||

By Steve Rudd: November 2017: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.

Go to: Main Bible Manuscripts Page