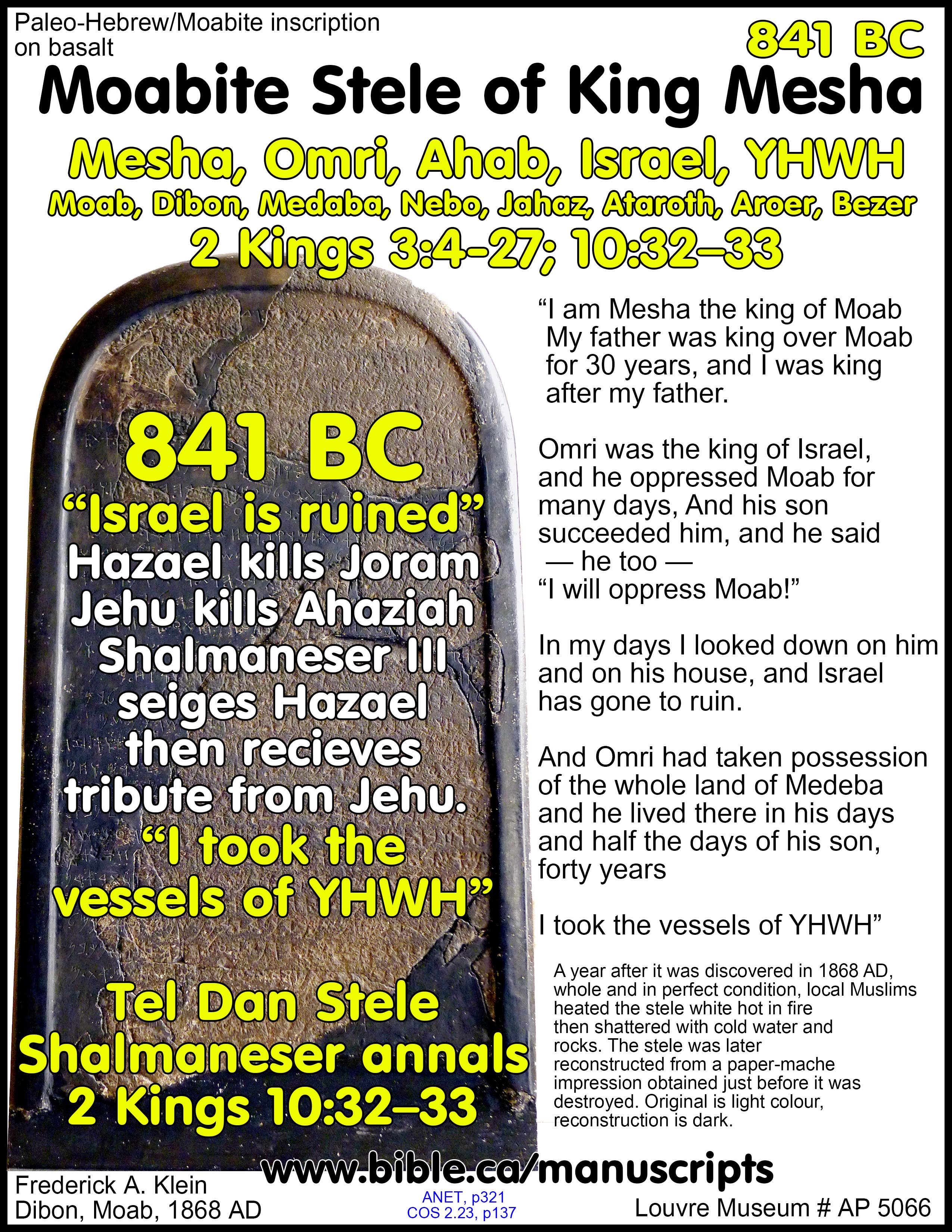

Moabite Stele of Mesha, king of Moab: 841 BC

Names: Mesha the sheep breeder, Omri, Ahab, Israel, YHWH

Places: Moab, Dibon, Medaba, Nebo, Jahaz, Ataroth, Aroer, Bezer

Scripture: 2 Kings 3:4-27; 10:32-33

See also: Detailed outline on Shalmaneser III

See also: Chronology of Elijah and Elisha

|

Moabite Stone (Mesha Stele) |

|

|

Date of inscription |

841 BC |

|

Annal years |

Omri – Jehu: 885-841 BC |

|

Glyptic object |

Paleo-Hebrew inscription on black basalt |

|

Discovery |

Frederick A. Klein at Diban, Moab 1868 AD |

|

Current location |

Louve Museum # AP 5066 |

|

Bible names and places |

Bible Names: Mesha the sheep breeder, Omri, Ahab, Israel, YHWH Bible Places: Moab, Dibon, Medaba, Nebo, Jahaz, Ataroth, Aroer, Bezer See: 2 Kings 3:4-27; 10:32-33 |

|

Historic events |

Submission of Moab to Omri in 885 BC and rebellion of Moab after the death of Ahab in 841 BC |

|

Digging up Bible stories! “I am Mesha the king of Moab… Omri was the king of Israel, and he oppressed Moab for many days, And his son Ahab) succeeded him, and he said “I will oppress Moab!” In my days (941 BC) I looked down on him and on his house, and Israel has gone to ruin. … And Chemosh said to me: “Go, take Nebo from Israel!” … I took it, and I killed [its] whole population, seven thousand male citizens … And from there, I took the vessels of yhwh” (Mesha Stone, 841 BC)

"What we read in the book, we find in the ground" |

Introduction:

1. Importance of the Moabite Stone (Mesha Stele) for Bible students:

a. It directly confirms the Bible stories in 2 Kings 3:4-27; 10:32-33

b. It documents the submission of Moab to Omri in 885 BC

c. It documents the rebellion of Moab after the death of Ahab in 841 BC

d. It documents the geography of the Bible!

2. Confirms the historical accuracy of the Bible:

a. Bible Names: Mesha the sheep breeder, Omri, Ahab, Israel, YHWH

b. Bible Places: Moab, Dibon, Medaba, Nebo, Jahaz, Ataroth, Aroer, Bezer

c. See: 2 Kings 3:4-27; 10:32-33

3. What you read in the book, you find in the ground!

I. About the Mesha Stele:

1. Content and connection with scripture:

a. “Apart from biblical material, Omri is known primarily from the Mesha Stela. According to that stela, Omri oppressed *Moab because Chemosh, Moab’s deity, was angry with his land. But in Omri’s son’s days (or possibly his grandson’s days) Mesha was able to regain control of all the Moabite territory. Mesha informs us that Omri had occupied the land of Mehadaba, and that he had built or rebuilt/fortified Ataroth and Jahaz. This indicates that Omri’s territory east of the Jordan River extended south to the Arnon tributaries. The Hebrew Bible records that Mesha revolted after the death of Ahab, but it gives little specific information about the earlier subjugation of Moab by Omri. Since Moab had been a vassal of Israel under David (2 Sam 8:2), perhaps the rulers of the northern kingdom were able to maintain control of Moab after the division of the monarchy. Alternatively, Omri himself may have moved more aggressively against Moab once his border disputes with Judah were resolved. The Hebrew Bible indicates that Mesha paid the king of Israel (possibly Omri and then Ahab) one hundred thousand lambs and the wool of one hundred thousand rams annually (2 Kings 3:4). Such a heavy tribute was ample cause for a revolt when the opportune time arrived, during Mesha’s reign over Moab.” (Dictionary of the Old Testament: Historical Books, p575, 2005 AD)

2. Discovery and how it got smashed into pieces:

a. “F. A. Klein was an Anglican minister, born in Alsace, who came to the Holy Land as a medical missionary in the mid-1800s. Although he lived in Jerusalem, he traveled widely on both sides of the Jordan, seeking to relieve pain and win converts. As a result of his work in Palestine, he spoke Arabic fluently and had many friends among the Arabs. Indeed, he was the only Westerner who could travel without danger in certain areas east of the Jordan, where the Bedouin were a law unto themselves. The Turkish government, although officially in control of the countryside, could not guarantee the safety of travelers. Since the Crusades, fewer than half a dozen Europeans had traveled in the barren desert areas of Transjordan. In the summer of 1868, Klein traveled on horseback to treat the sick in the area of ancient Moab, east of the Dead Sea. On August 19, 1868, Klein stopped at an encampment of Bedouin of the Banī Ḥamīdah tribe at Dhibān, Biblical Dibon, about three miles north of the Arnon River. He was accompanied by Zaṭam, the son of his friend Findī al-Fāiz, the sheikh of the Banī Ṣakhr, the most powerful tribe in Transjordan at the time, so he was guaranteed a most courteous reception. While there, he learned from the Bedouin of Dhibān of an inscribed stone lying in the nearby ruins of this ancient city. Klein asked to be taken to the stone, and his Bedouin friends gladly obliged. It is doubtful that he realized it at the time, but he was looking at the longest monumental stone inscription from ancient times that had ever come to light anywhere in Palestine. Today it is known as the Moabite Stone, or the Mesha Stele. The Moabite Stone is a black basalt stele; that is, an upright monument with a flat base and a rounded top. It is three feet high and about two feet wide. The inscription of 34 lines was incised on its front with a raised frame surrounding it on both sides and on its rounded top. When Klein first saw the Moabite Stone, it was lying on its back with the inscription face up. Klein lifted the stone to see if there was any writing on the back; there was none. Unable to read the inscription, he made a sketch of the monument and copied a few of the characters in his notebook. He then negotiated with the Bedouin for the purchase of the stone and obtained their oral agreement to sell it for 100 napoleons, worth about $400 at the time. Klein was the first European ever to see this ancient monument. Alas, he was also the last European to see it in an undamaged condition. On his return to Jerusalem at the end of August, Klein informed the consul of the Prussian government, J. Heinrich Petermann, of his discovery and of the Bedouin’s willingness to sell it. Petermann immediately sent a letter to the Berlin Museum asking for authorization to purchase the stone. He received an affirmative reply by telegram on September 15. Petermann first attempted to acquire the stone through Klein. Klein sent a letter asking for help to his friend Findī al-Fāiz, who as the sheikh of the Banī Ṣakhr was highly respected throughout Transjordan. Several weeks later the sheikh replied that he could do nothing in the matter. Klein’s use of an intermediary to follow through on his earlier agreement to acquire the stone unfortunately alerted the Bedouin to the intense European interest in the stone, and as a result they raised the original price tenfold, to 1,000 napoleons ($4,000). This was an outrageous price—unheard of Petermann then sought to acquire the piece through other avenues. He called upon Sābā Qa‘wār, an Arab teacher in Jerusalem, and asked him to go to Dhiban to negotiate with the Bedouin directly. Qa‘wār’s patient efforts over several months finally led to a mutually agreeable price: 120 napoleons (about $480). Qa‘wār resumed with a written agreement. But another difficulty soon arose. When Qa‘wār returned to Dhiban to arrange for the transportation of the stone to Jerusalem, the sheikh of the ‘Aṭwan, a neighboring tribe, refused to let the stone be shipped through his territory. In early November 1869, Qa‘wār resumed empty-handed to Jerusalem. Although the Germans tried to keep secret the discovery of the stone and their negotiations to acquire it, news inevitably leaked out. Among those who heard about it was Captain Charles Warren, who did survey work for the London-based Palestine Exploration Fund from 1867 to 1870. But, in order not to interfere with the German negotiations for its acquisition, Warren decided to do nothing. Not so, however, Charles Clermont-Ganneau. Clermont-Ganneau, who was later to distinguish himself as a scholar in Oriental studies, had arrived in Jerusalem at the age of 21, just a year before Klein’s discovery of the stone. Clermont-Ganneau was then serving as a young interpreter (dragoman) in the French consulate in Jerusalem. When he heard about the find, about October of 1869, he dispatched a trusted Arab friend, Salīm el-Qārī, to Dhiban to make inquiries about the stone. El-Qārī returned with a hand copy of seven lines that clearly demonstrated to Clermont-Ganneau the extraordinary significance of the inscription. Clermont-Ganneau then sent a man named Ya’qūb Karavaca to Dhibān to take a paper squeeze of the stone and to offer a purchase sum much higher than the one agreed upon between Sābā Qa‘wār and the Bedouin of Dhibān. The Bedouin allowed Karavaca to take a squeeze. This is done by placing a sheet of soft, wet paper on the inscribed stone and pressing the paper into the incisions with a brush. After the paper dries, it is peeled off and contains a reverse replica of the inscription with the letters in raised form. While Karavaca was waiting for his squeeze of the inscription to dry, a quarrel broke out among the local people that became so violent that Karavaca, who by this time had already received a spear-wound in the fracas, feared for his life. He tore the wet impression off the stone, jumped on his horse, and galloped away. The squeeze, in rags, tore into seven pieces. In the meantime, the Prussian consul Petermann, frustrated by what seemed like endless, unsuccessful attempts to obtain the stone, called upon the Turkish authorities to help him. At this time, Transjordan, like most countries of the Near East, was, as I have noted, at least nominally part of the Turkish empire. However, Petermann’s request for help from the Turkish authorities was followed by months of official negotiations before it led to any results. Finally, the Turkish authorities in Palestine were ready to send soldiers to Transjordan to obtain the stone by force. The people of Dhibān, however, hated the Turkish governor, who had made a punitive foray into their territory a year earlier. They therefore broke the stone into countless pieces by heating it in a fire and then pouring cold water on it while it was white-hot. The fragments were then distributed among the local Bedouin, who put them into their granaries to serve as talismans to guarantee the fertility of the soil. … After the stone was destroyed, the Germans seemed to lose interest in the monument. At least they made no efforts to obtain any of the fragments. But Clermont-Ganneau and Warren both tried to purchase as many fragments as possible. Clermont-Ganneau was the more successful. He obtained several of the large pieces and many small ones, in all 38 fragments containing a total of 613 letters out of a total of about 1,000. Warren, with the help of his Arab friends, was able to buy 18 small fragments containing 59 letters. One additional fragment was later purchased by a German scholar named Konstantin Schlottmann. The 57 pieces thus salvaged comprise approximately two-thirds of the original inscription. More than a century has now passed since the stone was destroyed, but we still don’t know what became of the many missing fragments comprising about one-third of the original monument. The Bedouin, probably unwilling to part with them, may have buried them and in the course of time forgotten where. Thus, the seven pieces of Karavaca’s extremely poor squeeze made for Clermont-Ganneau constitute the only copy of the complete inscription. The 38 fragments Clermont-Ganneau acquired went, in 1873, into the large Near Eastern collection of antiquities in the Louvre, the French national museum. The Palestine Exploration Fund, into whose possession Warren’s 18 small fragments had come, generously presented them to the Louvre as well. Later Professor Schlottmann’s daughter donated to the Louvre the fragment obtained by her father. With the seven pieces of Karavaca’s squeeze as a guide, Clermont-Ganneau was able to assemble the broken fragments and reconstruct almost the entire inscription, including the missing portions. So, in the end, this squeeze, imperfect as it was, became critical. For many years, this poor paper squeeze hung behind glass, side-by-side with the original stone in the Louvre and gave scholars an opportunity to check Clermont-Ganneau’s reconstruction. Even now, 118 years after its discovery, the Moabite Stone with its text of 34 lines is still the longest monumental inscription that has been discovered anywhere in Palestine, east or west of the Jordan River.” (Why the Moabite Stone Was Blown to Pieces, Siegfried H. Horn, BAR 12:03, 1986 AD)

II. Translations of the Paleo-Hebrew text of the Mesha Stone:

1. Line by line translation #1: COS 2.23, p137

|

Introduction and Identification (1–3a) I am Mesha, the son of Chemosh[-yatti], the king of Moab, the Dibonite [Dibon was capital of Moab]. My father was king over Moab for thirty years, and I was king after my father.

Occasion for the Erecting of the Stela (3b–4) And I made this high-place for Chemosh [National god of Moab] in Karchoh, […] because he has delivered me from all kings (?), and because he has made me look down on all my enemies.

Introduction to the Part on Military Achievements (5–7a) Omri was the king of Israel, and he oppressed Moab for many days, for Chemosh was angry with his land. And his son succeeded him, and he said — he too — “I will oppress Moab!” In my days did he say [so], but I looked down on him and on his house, and Israel has gone to ruin, yes, it has gone to ruin for ever! [cf: "In those days the Lord began to cut off portions from Israel; and Hazael defeated them throughout the territory of Israel: from the Jordan eastward, all the land of Gilead, the Gadites and the Reubenites and the Manassites, from Aroer, which is by the valley of the Arnon, even Gilead and Bashan." (2 Kings 10:32-33]

The Return of the Land of Medeba (7b–9) And Omri [885-874 BC] had taken possession of the whole la[n]d of Medeba, and he lived there (in) his days and half the days of his son [Ahab], forty years [841 BC when Jehu paid tribute to Shalmaneser III and Hazael kills two kings], but Chemosh [resto]red it in my days. And I built Baal Meon, and I made in it a water reservoir, and I built Kiriathaim.

The Conquest of Ataroth (10–13) And the men of Gad lived in the land of Ataroth from ancient times, and the king of Israel [Omri] built Ataroth for himself, and I fought against the city, and I captured it, and I killed all the people [from] the city as a sacrifice (?) for Chemosh and for Moab, and I brought back the fire-hearth of his Uncle (?)12 from there, and I hauled it before the face of Chemosh in Kerioth, and I made the men of Sharon live there, as well as the men of Maharith.

The Destruction of Nebo (14–18a) And Chemosh said to me: “Go, take Nebo from Israel!” And I went in the night, and I fought against it from the break of dawn until noon, and I took it, and I killed [its] whole population, seven thousand male citizens (?) and aliens (?), and female citizens (?) and aliens (?), and servant girls; for I had put it to the ban for Ashtar Chemosh.16 And from there, I took th[e ves]sels of yhwh, and I hauled them before the face of Chemosh.

The Conquest of Jahaz (18b–21a) And the king of Israel [Ahab] had built Jahaz, and he stayed there during his campaigns against me, and Chemosh drove him away before my face, and I took two hundred men of Moab, all its division (?), and I led it up to Jahaz. And I have taken it in order to add it to Dibon.

Mesha’s Building Activities at Karchoh (21b–25) I have built Karchoh, the wall of the woods and the wall of the citadel, and I have built its gates, and I have built its towers, and I have built the house of the king, and I have made the double reser[voir for the spr]ing (?) in the innermost part of the city. Now, there was no cistern in the innermost part of the city, in Karchoh, and I said to all the people: “Make, each one of you, a cistern in his house.” And I cut out the moat (?) for Karchoh by means of prisoners from Israel.

Other Building Activities (26–27) I have built Aroer, and I made the military road in the Arnon. I have built Beth Bamoth, for it was destroyed. I have built Bezer, for [it lay in] ruins.

First Conclusion (28–29) [And the me]n of Dibon stood in battle-order,23 for all Dibon, they were in subjection. And I am the kin[g over the] hundreds in the towns which I have added to the land.

Other Building Activities (30–31a) And I have built [the House of Mede]ba and the House of Diblathaim and the House of Baal Meon, and I brought there […] flocks of the land.

Battle at Horonaim (31b–34) And Horonaim, there lived […] And Chemosh said to me: “Go down, fight against Horonaim!” I went down […] [and] Chemosh [resto]red it in my days. and […] from there […] […] […]

Second Conclusion (34-) And I … COS 2.23, p137 |

2. Translation #2: ANET, p 321

|

I (am) Mesha, son of Chemosh-[ … ], king of Moab, the Dibonite—my father (had) reigned over Moab thirty years, and I reigned after my father,—(who) made this high place for Chemosh in Qarhoh [ … ] because he saved me from all the kings and caused me to triumph over all my adversaries. As for Omri, (5) king of Israel, he humbled Moab many years (lit., days), for Chemosh was angry at his land. And his son followed him and he also said, “I will humble Moab.” In my time he spoke (thus), but I have triumphed over him and over his house, while Israel hath perished for ever! (Now) Omri had occupied the land of Medeba, and (Israel) had dwelt there in his time and half the time of his son (Ahab), forty years; but Chemosh dwelt there in my time.”

“And I built Baal-meon, making a reservoir in it, and I built (10) Qaryaten. Now the men of Gad had always dwelt in the land of Ataroth, and the king of Israel had built Ataroth for them; but I fought against the town and took it and slew all the people of the town as satiation (intoxication) for Chemosh and Moab. And I brought back from there Arel (or Oriel), its chieftain, dragging him before Chemosh in Kerioth, and I settled there men of Sharon and men of Maharith. And Chemosh said to me, “Go, take Nebo from Israel!” (15) So I went by night and fought against it from the break of dawn until noon, taking it and slaying all, seven thousand men, boys, women, girls and maid-servants, for I had devoted them to destruction for (the god) Ashtar-Chemosh. And I took from there the [ … ] of Yahweh, dragging them before Chemosh. And the king of Israel had built Jahaz, and he dwelt there while he was fighting against me, but Chemosh drove him out before me. And (20) I took from Moab two hundred men, all first class (warriors), and set them against Jahaz and took it in order to attach it to (the district of) Dibon.”

“It was I (who) built Qarhoh, the wall of the forests and the wall of the citadel; I also built its gates and I built its towers and I built the king’s house, and I made both of its reservoirs for water inside the town. And there was no cistern inside the town at Qarhoh, so I said to all the people, “Let each of you make (25) a cistern for himself in his house!” And I cut beams for Qarhoh with Israelite captives. I built Aroer, and I made the highway in the Arnon (valley); I built Beth-bamoth, for it had been destroyed; I built Bezer—for it lay in ruins—with fifty men of Dibon, for all Dibon is (my) loyal dependency.”

“And I reigned [in peace] over the hundred towns which I had added to the land. And I built (30) [ … ] Medeba and Beth-diblathen and Beth-baal-meon, and I set there the [ … ] of the land. And as for Hauronen, there dwelt in it [.… And] Chemosh said to me, “Go down, fight against Hauronen. And I went down [and I fought against the town and I took it], and Chemosh dwelt there in my time.…” (ANET, p 321) |

Conclusion:

1. The Moabite Stone (Mesha Stele) confirms the historical accuracy of the Bible:

a. Bible Names: Mesha the sheep breeder, Omri, Ahab, Israel, YHWH

b. Bible Geography is confirmed by naming cities and places: Moab, Dibon, Medaba, Nebo, Jahaz, Ataroth, Aroer, Bezer.

c. See: 2 Kings 3:4-27; 10:32-33

2. What you read in the book, you find in the ground!

3. Find me a church to attend in my home town this Sunday!

By Steve Rudd: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.