'Edomite', `Negbite' And 'Midianite' Pottery From

The Negev Desert And Jordan:

Instrumental Neutron Activation Analysis Results

J. Gunneweg

1991 AD

(Edomite, Negev, Midianite Pottery: Neutron Activation Analysis, Gunneweg, 1991 AD)

Archaeometry 33, 2 (1991), 239-253. Printed in Great Britain

Department of Archaeometry, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel

TH. BEIER, U. DIEHL, D. LAMBRECHT and H. MOMMSEN

Institut fur Strahlen- and Kernphysik, University of Bonn, Bonn, F.R.G.

INTRODUCTION

Little analytical work has been done in archaeology concerning the provenance of ceramics found in the Negev desert in Israel ('Amr 1987; Gunneweg et al. forthcoming) in contrast to that on major archaeological sites in central and northern Israel.

The Negev, however, is an interesting area of study, since it was traversed and inhabited in ancient times, as attested by the remains of material culture found in many ancient fortresses, settlements and farms. In this study we will focus on `Negbite' and `Edomite' pottery found in the Negev and on the mountain plateau of Jordan, as well as on 'Midianite' pottery found at Timna; this last has for over 30 years been the subject of controversy with regard to its importance in explaining purported inter-regional contacts with neighbouring countries.

According to the Bible, the kings of Judah were involved during the eighth to sixth century BC

[wrong: the bible says that Solomon expanded control in 950 BC] in keeping the Negev defensible by holding this vast area populated as a buffer zone against unwanted wandering tribes who appeared to get too close to the territory of Judah and in protecting their interests by safeguarding the barren caravan trade routes which connected the 'Kings Road' (Arabia-Petra-Damascus) with Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea. Large quantities of imported pottery from the Aegean and Cyprus in Palestine, Jordan and Midian in north-west Arabia bear witness to this trade (Franken 1975).One of the feared foreign, ethnic groups was the arch-enemy of Judah, the Edomites (Isa. 34: 5-15; Jer. 49: 7-22; Obad. verse 18; Ezek. 25: 12--14), who had their kingdom, Edom, east of the line Sodoma-Eilat, from Wadi el-Hesa to Wadi Hismeh in Jordan. Archaeologists have wondered whether Edomites settled as a minority in the Negev (or a part of it) among a Judahite majority hostile to them. Archaeologically, an occupying force leaves its traces. One of the traces ascribed to the Edomites consists of an easily discernible type of painted and plain pottery, characterized by form, finish and decoration (Oakeshott 1978 and 1983; Bennett 1966, 1983 and 1984). Its painted repertory, which is of interest here because it cannot be confused with any other kind of painted pottery, consists primarily of bowls, kraters and plates. It is characterized by dentillated relief bands stuck to the outside of kraters, while sometimes accompanied by ledge handles in the form of a knuckle bone. Its fabric is usually of a reddish-buff colour and its surface is often highly burnished, resembling a burnished slip. Its geometric decoration consists of painted horizontal bands bridged by vertical strokes, and 7-shaped (cross) lines, sometimes filled with a painted grille in red and black.

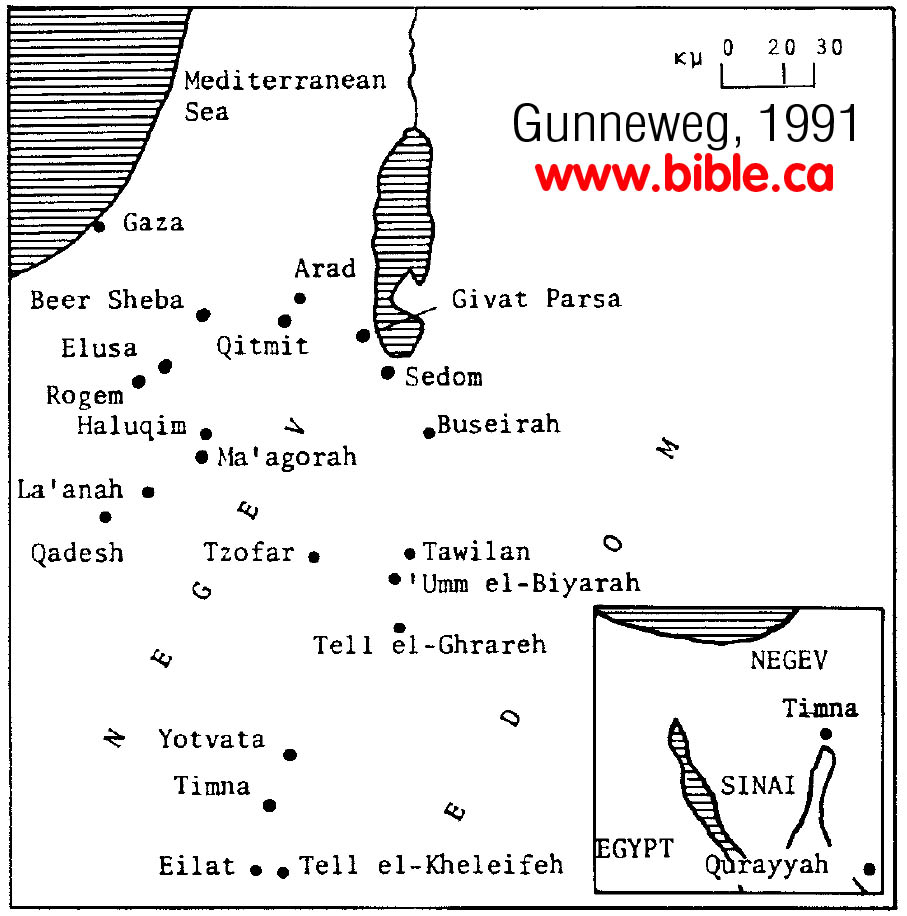

Figure 1 Location map me the sites in the Neget. and Jordan pertinent to this study.

This pottery was first found at Tell el-Kheleifeh, near Aqaba in Jordan, by N. Glueck in 1934 who called it Edomite' (Glueck 1967. fig. 2) and who dated it to the e. thirteenth to sixth century BC. In 1968, C.-M. Bennett found similar ware in Iron Age II Tawilan, near Petra ( Bennett 1984). Furthermore, it was found at Edomite sites such as 'Umm el-Biyarah (a few sherds only), Tell el-Ghrareh, and Buseirah (Hart 1988; Bennett 1983).

In Israel, painted 'Edomite' ware has been found in rather small quantities at several sites in the Negev (Mazar 1985; Beit-Arieh 1989). Most of these sites are Iron Age II fortresses, some are farms, others single buildings. All are situated along water springs on sites overlooking an ancient major network of desert roads and trails, such as at Iron Age II Horvat Qitmit, Qadesh Barnea, Horvat Rogem, and Fort La'anah. All sites pertinent to this study are shown on Figure 1.

Two sites have provided most of the `Edomite' pottery so far found in the Negev: the shrine complex of Horvat Qitmit (north-east Negev) and Qadesh Barnea (east Sinai). The sites differ greatly in architectural layout: the Horvat Qitmit shrine consists of a few buildings, whereas Qadesh Barnea is a large fortress. Analytical work performed on the ceramics found at the shrine of Horvat Qitmit was described at some length in a previous publication (Gunneweg and Mommsen 1990). The Iron Age II fortress of Qadesh Barnea (nowadays called Tell 'Ein el-Qudeirat) is located in Wadi el 'Ein, a well ('Ein) which has fed the largest oasis of the southern Negev as well as northern Sinai from early times until the present (Dothan 1965, 134; Woolley and Lawrence 1914. 69-71; Cohen 1983, 93-4). The Qadesh Barnea fortress has three complexes corresponding to phases spanning about 300 years; they are called the upper, middle and lower fortress. `Edomite' pottery has only been found within the ashes from the conflagration of the upper fortress in the context of Cypro-Phoenician juglets, a collection of tens of handmade, coarse `Negbite' pots, and a predominance of Judahite vessels reminiscent of the seventh to sixth century BC (Cohen 1983, 100).

The quantity of painted `Edomite' pottery at the remaining sites of the Negev does not exceed 0.1% of the total amount of excavated pottery fragments, whereas at Qadesh Barnea it amounts to 1 %, thus a factor of 10 higher than elsewhere; at the Qitmit shrine it constitutes the majority of all ceramics found there (over 200 vessels: pers. comm. I. Beit-Arieh).

Another type of pottery with stylistic features similar to those of `Edomite' ware was found by B. Rothenberg in the Hathor shrine at Timna, which was dated by two cartouches of Seti I and Ramses V, ranging in time from 1318 to 1156 BC. Rothenberg called the painted pottery 'Egyptian' because of the 'Egyptian' connection (Rothenberg 1972 and 1988; Glueck 1935, 152). In 1968, during Parr's survey of northern Hejaz in Arabia, J. Dayton found similar painted pottery at Hereibe (ancient Dedan) and at Qurayyah (Midian) (Parr et al. 1970) and called it 'Midianite' while dating it to correspond to that found at the Hathor shrine in Timna (c. fourteenth to twelfth century BC). This hand- and wheelmade pottery was also found at various copper smelting sites at Timna of which three are particularly well dated, that is smelting sites 2 and 3, and a group of undisturbed smelting sites on top of a plateau, Slaves Hill, which is difficult of access and is considered to have been occupied by mining Midianites. Our survey there revealed pottery fragments, some of which were painted `Midianite' while others were of a type of ceramic which is slipped in buff, red, green and blue tints. It is the latter which has been classified as 'Egyptian faience-like' ware (Rothenberg 1972 and 1988) and 'Midianite' by others (Parr et al. 1970). The chronology of these wares at Timna possibly covers the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age I periods (1318-1156 BC), based on datable Egyptian cartouches, scarabs and other finds.

Finally, we were interested in a handmade, sandy and coarse ceramic which the inhabitants of the Negev have manufactured for over three millennia without interruption, that is `Negbite' ware. It comprises primarily cooking pots, kraters and bowls.

The purpose of this study is to establish the origin of the three abovementioned different pottery styles in order to shed some light on important inter-regional contacts between, on the one hand, the Negev and Timna and, on the other hand, Egypt, Midian and Edom. These different pottery repertories are listed in Table 1 according to chronological period and style and with the names used in the present study.

SAMPLING

The sampling for this project was done selectively so that the results might be representative of stylistically similar (not analysed) pottery of painted `Edomite', plain `Negbite' and `Midianite' ware found in the Negev. Forty samples of Iron Age II, plain as well as painted, `Edomite' ware were taken from Horvat Qitmit, Qadesh Barnea, Givat Parsa and Horvat Rogem, all in the Negev, and from Buseirah and Tell el-Ghrareh in Jordan. The Qadesh Barnea sample constituted about 50% of all painted `Edomite' ware found there.

Twenty-seven samples of coarse handmade `Negbite' ware (ranging in date from the thirteenth century BC to the seventh century AD) were taken from vessels and sherds found

Table 1 Early Iron Age I and Late Iron Age II pottery found north and east of the Sinai peninsula

Ceramic Period

Late Bron:e Age II-Iron Age 1 Iron Age 11

Coarse ware 'Negbite' 'Negbite'

Fine ware Plain `Edomite'

Slipped 'Egyptian-faience'

Painted 'Midianite' `Edomite'

at eight different Negev sites. Furthermore, 14 vessel fragments of `Midianite'/`Egyptian faience-like' pottery of the fourteenth to twelfth century BC, found during our survey of Timna's Slaves Hill, were sampled.

As regards reference material, we were lucky already to have available (Gunneweg and Mommsen 1990) a set of pottery wasters from Israel's Negev (Beer Sheba) and Petra in Jordan (Gunneweg et al. forthcoming) so that a match of pottery with these wasters would be site-specific. An extra kiln waster from Elusa in the western Negev (N 127) was analysed as well.

Three groups of Iron Age II pottery served as additional reference material. One group is stylistically local to Beer Sheba (unpublished data from the Berkeley data bank), whereas two others of plain 'Edomite' ware are chemically local to Tawilan and 'Umm el-Biyarah in Jordan (Gunneweg et al. forthcoming). Finally, four loomweights of unbaked clay, found at Qadesh Barnea and Horvat Rogem, seemed logical candidates for obtaining a local chemical composition for these sites or their immediate environment, because loomweights are usually made locally from the clay available at a site. However, the loom weights did not live up to our expectations. The analysis of clay has its own difficulties: clay used for loomweights is not necessarily identical with that used for the manufacture of pottery (Widemann et al. 1975, 75).

All 81 samples are listed in Table 2 with their name, code number and registration number, followed by the type of vessel, find spot and date, and, as the result of our INAA work, origin; the dilution factors used (see below) are also given. The code numbers will be cited for ease of reference.

ANALYTICAL METHOD

This study was conducted with the aid of instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA) and carried out at Bonn (Mommsen et al. 1987). INAA is a technique which determines quantitatively a multi-elemental chemical composition (a chemical 'fingerprint') of a ceramic independently of how it 'looks' to the eye of an archaeologist. INAA has been recorded as being successful in tracing the chemical 'fingerprint' of ceramic artefacts to their source(s).

Tracing pottery requires the accumulation of as many elemental abundances as possible because some of the elemental concentrations could be accidentally similar in different clays. The higher the precision of an analytical method, the better the chance of obtaining a unique chemical 'fingerprint' of an artefact.

The method is virtually the same as that which has been already described extensively in Perlman and Asaro 1969. INAA at Bonn measures 36 elements present in pottery of which 14 are usually taken to differentiate one ceramic from another. These 14 are in most cases measured with small statistical errors and are considered to be geochemically uncorrelated. They are marked by an asterisk (*) in Table 4. The reason that usually more than 14 elements are shown in our tables is that the additional values are available and are sometimes useful for analytical work in other laboratories.

RESULTS

With the INAA data from all 81 sherds in this study in a data bank, the search for groups of sherds of similar composition is done according to two different grouping concepts.

(1) The simplest and most reliable method is a stepwise search through the entire data bank calculating, for each sherd, a 'goodness of fit' value (x2) to a given composition. This direct search has been described at length in Mommsen et al. (1988). It accounts for experimental errors and a possible dilution of potter's clay due to pottery-making practices. A further advantage is that the x2 value can be normalized, that is similar concentrations result in values of x2 around 1. Single outliers in the bank are recognized easily by larger x2 values. The search can be conducted either by comparing pairs of individual sherds or by starting with predefined group means and comparing individual sherds to these means. In the latter case, low x2 values will result if the single elemental concentrations match the mean values of the group. Where 'non-group' members are incorporated into a predefined group, the group means, and hence the x2 values, are iteratively recalculated. Table 3 shows the x2 values for the Tdom' group of 25 sherds as well as the values for the other 'non-group-member' sherds. A value of 2.5 was chosen as the cut-off.

(2) Multivariate cluster analyses using the x2 measure or the squared euclidian distance similarity measures and Ward's cluster criterion are also successful in locating the groups, but only if outliers are taken out of the data bank first. The presence of outliers in most cases disturbs the multivariate statistical grouping.

A dendrogram resulting from such an analysis placing only group members in the data bank and using the above-mentioned 14 elements is shown on Figure 2. The dendrogram was produced with Ward's method using the x2 dissimilarity measure. Plotted on the vertical axis is In (x2+ 1) (Mommsen et al. 1988).

Also included in our data bank are concentration values of single wasters of pottery from different sites, as well as group values of pottery of known origin. Their positions are marked on the dendrogram. A group of ten measurements of coal fly ash (National Bureau of Standards, Washington, homogenized standard reference material 1633a) is shown to indicate the size of the dissimilarity parameter (the vertical axis of the dendrogram) of samples of identical composition and to define a lower boundary for the horizontal grouping cut-off line. According to our stepwise search this cut-off line is placed at such a position that four groups result (see Figure 2). The grouping in the dendrogram is the same as that obtained with the iterative procedure which is summarized below the dendrogram. The only exception (one sherd) is indicated by an arrow. Other clustering methods, such as average linkage and other similarity measures, such as the euclidian distance, do not show such good agreement in grouping.

244 J. Gunneweg, Th. Beier, U. Diehl, D. Lambrecht and H. Mommsen

Table 2 Pottery samples of 'Edomite', 'Negbite' and 'Midianite' ware submitted to instrumental neutron activation

analysis ( INAA) and discussed in this paper

Code Registration Type of vessel Find spot Century Origin Average

no. no. according dilution

to INAA factor

'Edomite'

Ql* 1523.1 Ostracon (Horvat 'Liza) 7-6 BC N-E Negev 0.92

Q3* 518'1 Ostracon incised with 'QAUS' I N-E Negev 0.90

Q4 214;4 Anthropomorphic vase I N-E Negev 1.01

Q5 22712 Zoomorphic stand I N-E Negev 0.96

Q6 190'2 Bird cultstand I N-E Negev 1.03

Q7 252/5 Pomegranate cultstand I N-E Negev 1.06

Q8 293'1 Pomegranate cultstand I N-E Negev 1.02

Q9 284/1 Jar with hand and sword I N-E Negev 1.03

Q12 380/1 Anthropomorphic figurine I N-E Negev 0.94

Q13 174/3 Stand with elbow and arm I N-E Negev 1.05

Q15 210/4 Cultstand with ledges I N-E Negev 1.01

Q17 348/2 Holemouth jar I N-E Negev 0.94

Q18 291/9 Cooking pot I N-E Negav

-

Q20 262/2 Bowl with cut-out everted rim I N-E Negev 0.94

Q22 214/7 Painted holemouth jar I N-E Negev 0.96

Q23 250/4 Bowl with folded rim I N-E Negev 0.95

Q24 173:1 Three-horned goddess head I N-E Negev 0.97

NI 1400/2912 Krater II 6 BC N-E Negev 1.08

N2 9011917 Bowl II N-E Negev 0.93

N3 427/851 Deep bowl II N-E Negev 1.07

N4 402,824 Krater with ledge 11 N-E Negev 1.01

N5 427/851 I Deep bowl II N-E Negev 1.10

N6 4021825 Platter II N-E Negev 0.94

N7 427.858 Krater, dentillated ledge II N-E Negev 1.03

N8 42718592 Krater, dentillated ledge II N-E Negev 1.10

N9 402 724 I Bowl II N-E Negev 1.01

NIO 2159/4130,1 Krater II N-E Negev 0.99

N11 427;859:3 Deep bowl, dentillated II N-E Negev 1.11

NI2 2150/4107 '1 Krater II N-E Negev 0.97

N13 2150'4107,2 Bowl, knucklebone handle II N-E Negev 0.99

N14 21594130;2 Bowl II N-E Negev 1.01

N16 402;'724;2 Krater II N-E Negev 1.04

NI7 8194 Krater Rogem 7 BC N-E Negev 1.01

N22 1 16 1 Jar, ledge handle Parsa 7 BC Unknown

-

N23 1/16;2 Bowl, everted rim Parsa Edom 1.00

NI35 A II 2-2 Cooking pot 1, grey Ghrareh 7 BC Edom 1.09

N136 A H 2-2 Cooking pot 2, r br Ghrareh Edom 1.11

N137 A II 4-2 Cooking pot 9, r br Ghrareh Edom 1.08

NI38 R II 2.5 Jug, 051 vvh on buff Buseirah Edom 1.05

N139 R II 3.33 Small bowl, cr,ware Buseirah Unknown -

Weghite'

N24 473'1034.2 Bowl, buff Parsa 7 BC Unknown

N25 473/841/2 Bowl, cream Parsa N-W Negev 1.01

N26 39/53/2 Bowl, cream Parsa N-W Negev 1.04

N29 Site 30/ 1 Bowl Timna 14-12 BC Edom 0.92

Table 2 (continued)

Code Registration Type of vessel Find spot Century Origin Average

no. no. according dilution

to INAA factor #

N30 Site 30/2 Bowl Timna Edom 1.20

N31 1 Bowl Horvat Ma'agorah Edom 0.94

N32 1 Bowl La'anah Unknown

N33 1 Bowl Fort Yotvata 3 AD Edom 0.98

N48 794/2491/1 Krater (middle fort) II 7-6 BC Unknown

N49 186/471/1 Bowl (upper fort) II N-W Negev 0.97

N65 6292/8580 Cooking pot (lower fort) II Edom 1.05

N66 6294/8583/1 Oil lamp (lower fort) II Unknown

N67 6294/8583/2 Small bowl (lower fort) II N-W Negev 1.04

N68 6139/8280 Bowl (middle fort) II N-W Negev 0.92

N69 3135/8278/8 Bowl (middle fort) H N-W Negev 1.02

N70 482/896/2 Bowl (middle fort) II Unknown

N71 186/471/3 Kra ter, (upper fort) II N-W Negev 1.10

N72 501/961 Small bowl (upper fort) II N-W Negev 0.98

N74 1/1 Bowl (early Arabic) Tzofar 7 AD Edom 1.36

N84 (9) L.1 Sherd Tzofar Unknown

N104 Survey V-shaped bowl, flat rim III 14-12 BC Edom 0.89

N105 Survey V-shaped bowl III Edom 1.09

N106 Survey S-shaped krater HI Unknown --

N109 Survey V-shaped bowl, flat rim III Edom 0.78

N114 Survey Bowl III Unknown

N130 Survey Bowl Haluqim 10 BC Unknown

N131 Survey Bowl Haluqim Edom 1.33

`Midianite'

N27 Site 2/1 'Midianite' bowl III 14-12 BC Arabia 0.98

N28 Site 2/2 'Midianite' platter III Arabia 1.03

N107 Survey S-shaped krater III Edom 1.11

N108 Survey 'Midianite' stopper III Edom 0.86

N110 Survey Krater with bulging rim III Edom 0.87

N111 Survey Krater, red burnished slip III Edom 0.79

N112 Survey Bowl with red slip inside III Unknown

N1 I3 Survey Coarse bowl HI Unknown

N115 Survey Bowl with triangular rim III Edom 0.85

NI 16 Survey Sherd, highly red burnished III Edom 1.01

NI17 Survey Bowl with green/white slip III Edom 0.89

NI 18 Survey Jug with green/blue slip III Edom 0.85

N119 Survey Sherd, red burnished III Edom 0.94

N120 Survey Krater, ring base bottom III Edom 1.20

Reference

N127 Survey Pottery kiln waster Elusa 2 AD N-W Negev

# The average dilution factor of each single sample obtained by using 14 elements (see text for explanation). * Origin determined in Gunneweg and Mommsen 1990, 13.

Horvat Qitmit shrine of the seventh century BC.

II Qadesh Barnea fortress of the seventh-sixth century BC.

III Survey conducted on Slaves Hill and at smelting sites 2 and 30 at Timna.

Table 3 x2 values calculated with the 'Edom' group mean values ( number of samples between 0 and 1 x 2, etc.), using

14 elements ( marked with an asterisk in Table 4)

0 1 2 3 4 5

No. of samples 14 10 1 (Edom group (25))

1 10 16 6 (N-E Negev (33))

1 2 3 2 (N-W Negev (8))

2 (Arabia (2))

The grouping results obtained by statistical methods are finally verified by inspection of the concentration values themselves. In Table 4 the concentrations of 26 elements are shown for the four groups of pottery which we shall designate north-east Negev, north-west Negev, Edom and Arabia. For each group its mean values (M) and its root-mean-square deviation (sigma) expressed as a percentage are listed. All columns of Table 4 show the data of pottery groups after correction by the 'best relative fit factor', called also the 'dilution factor', to each sample of the group (Mommsen et al. 1988). This dilution factor is obtained for each sample by a fit to the group values using the aforesaid 14 elements in pottery (marked by an asterisk in Table 4). It primarily corrects for differences in pottery-making techniques, such as levigation and tempering of the potter's clay, and to a lesser extent it also corrects for certain experimental errors such as differences in water content of the samples, weighing errors and

1 L-I 1,--I

8 9 10 11 12

Figure 2 Dendrogram based on './2 dissimilarity measure' of the four primary pottery groups, and of reference material from Petra, Beer Sheba and of two Edomite sites, as well as coal fly ash (CFA) measurements for defining a lower boundary for the horizontal grouping cut-off line. 1: single pottery waster from Dust); 2: group of Iron Age II pottery from Beer Sheba; 3: single pottery waster from Beer Sheba: 4.' single piece which belongs to north-west Neger group: 5: group of pottery from 'Umm el-Biyarah (Jordan); 6: group of pottery from Tawilan ( Jordan): 7.. fire pottery wasters from Petra (Jordan): 8: north-west Negev group: 9.. north-east Neger group; 10: combined Edomite pottery ( in text refered to as 'Edom' group): 11: two pieces from Arabia; 12: ten measurements of coal .fly ash.

Table 4 Elemental abundances corrected for the 'best relative fit' factor offPur chemical groups of `Edomite', 'Negbite' and 'Midianite' pottery found in the Negev #

Element N-E Neger Buseirah Ghrareh N-W Neger Elusa waster Edon mixed3 Petra Nabataean Tawilan Timna 'Midianite'

•Edontite. pottery I 'Edomite'" 'Negbite' pottery wasters 'Edomite' pottery 'Midianite' pottery mixed sites4

(33 samples) (4 samples) (8 samples) ( 1 sample) (25 samples) (5 samples) (5 samples) (2 samples) (10 samples)

M (sigma ( % )) M (sigma) ( % ) ) M (sigma (%) ) exp. error M (sigma ( %) ;14 ( sigma ( %)) M (.sigma ( %) 1 M M ( sigma (%))

Ba 684 (46) 243 (64) 421 (19) 459 (1.4) 320 (75) xx xx 853 xx

Ca% 6.22 (28) xx 12.3 (12) 10.4 (1.4) 2.95 (78) xx 3.1 (32) 0.6 0.3 (13)

Ce* 65.4 (4.3) 51.7 (8.6) 51.3 (2.2) 55.9 (0.7) 55.6 (7.2) 51.8 (3.5) 62.6 (15) 150 xx

Co* 20.5 (4.3) 17.6 (6.4) 12.5 (16) 15 (0.7) 17.3 (15) 19.2 (12) 18.6 (9.1) 8.31 6.99 (9.3)

Cr* 124 (6.1) 104 (13) 88 (5.9) 87 (1) 135 (18) 101 (4.6) 123 (8.1) 130 143 (5.6)

Cs* 1.72 (12) 3.22 (29) 1.38 (4.1) 1.58 (4.1) 3.72 (24) 3.81 (6.4) 3.70 (11) 6.28 7.3 (9.6)

Eu 1.47 (3.4) 1.15 (9.3) 1.09 (2.8) 1.14 (1.9) 1.27 (8.9) 1.21 (3.9) 1.47 (9.5) 1.91 xx

Fe%* 4.55 (3.2) 4.28 (0.8) 3.08 (6.9) 3.37 (0.4) 4.34 (9.1) 4.52 (3.1) 5.04 (10) 3.79 5.23 (5.5)

Gd 5.76 (11) 5.12 (12) 4.43 (19) 4.24 (12) 4.98 (14) xx xx 8.1 xx

Hf* 9.43 (8.1) 4.79 (10) 6.52 (15) 8.66 (0.9) 4.86 (16) 6.21 (20) 6.17 (14) 3.77 3.9 (9.0)

K% 1.9 (28) 1.73 (27) 2.27 (9) 1.27 (2.8) 2.13 (16) xx xx 2.95 xx

La* 30.7 (6) 22.4 (8.9) 24.9 (2.6) 26.8 (1.3) 25.8 (7.2) 24.1 (6) 27.7 (11) 73.8 75.8 (6.3)

Lu 0.47 (4.8) 0.39 (5.2) 0.33 (2.4) 0.36 (3.3) 0.42 (6.7) 0.34 (9.9) 0.45 (8.9) 0.62 0.57 (5.3)

Na% 1.28 (21) 0.15 (63) 1.32 (9.8) 0.92 (1.4) 0.63 (90) xx 0.17 (19) 0.36 0.31 (9.7)

Nd 28.4 (4.5) 22.6 (9.1) 23.3 (3.2) 24.9 (1.8) 24.9 (7.9) 23.6 (5.3) xx 61.7 xx

Ni 72 (29) 44.6 (7.5) 65 (17) 59 (11) 49 (24) 41 (35) 42 (24) 35 18 (83)

Rb* 50 (7.1) 51.8 (5.3) 41 (4.9) 44 (3.3) 69 (18) 78 (31) 86 (34) 171 187 (9.6)

Sb 0.41 (14) 0.28 (12) 0.43 (14) 0.34 (12) 0.34 (24) xx xx 0.25 xx

Set 15.1 (2.8) 19.6 (17) 10.4 (2.1) 11.3 (0.2) 19.8 (13) 18.4 (4.1) 22.6 (8) 24.7 25.6 (3.1)

Sm 5.86 (3.5) 4.58 (0) 4.53 (1.9) 4.75 (0.6) 5.05 (8.4) 4.84 (2.1) 5.87 (11) 10.1 xx

Tat 1.29 (4.3) 0.74 (9.9) 0.98 (5.6) 1.05 (1.1) 0.80 (19) 0.72 (4.5) 1.24 (10) 1.42 1.47 (2.0)

Tb 0.86 (4.4) 0.66 (13) 0.63 (2.7) 0.76 (3.8) 0.69 (11) 0.67 (4) xx 1.07 xx

Th* 7.76 (5) 6.82 (1.8) 6.2 (2.4) 6.84 (0.8) 7.28 (7.6) 7.00 (3.6) 8.21 (I 1) 22.7 23.1 (5.2)

Ti%* 0.81 (II) 0.44 (7.9) 0.45 (7.7) 0.53 (3.4) 0.49 (11) 0.46 (7.1) 0.68 (7.4) 0.55 0.66 (1.5)

I.J* 2.52 (II) 1.69 (18) 2.71 (12) 2.31 (1) 2.30 (25) 2.56 (9.9) 1.96 (9.7) 4.32 4.71 (5.5)

Yb* 2.98 (5.2) 2.53 (7.8) 2.31 (2.3) 2.67 (1) 2.63 (8.6) 2.51 (9.3) 2.99 (8) 4.28 xx

(I) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9)

it All concentrations are in ppm if not stated otherwise.

* Uncorrelated elements with best counting statistics.

'Edomite' pottery from the Negev (Horvat Qitmit, Qadesh Barnea and Horvat Rogem).

2 'Edomite' pottery from Jordan.

3 Mixed group of 'Edomite', 'Negbite', 'Midianite' and 'faience-like' pottery from Ghrareh, Timna, Qadesh Barnea, Buseirah, Givat Parsa, Yotvata, Tzofar, Ma'agorah and Halugim, all with a similar chemical pattern.

4 Timna and Qurayyah: unpublished results of the Berkeley INAA data bank TIM 7, 8, 24, 29, 31, 34; QRY 2, 6, 7, 9.

neutron flux inhomogeneities during irradiation. The adjustment for dilution can only be explained where clays are really similar.

The north-east Negev, north-west Negev and Arabia groups comply with the criterion for homogeneity of a group which we have established, that is the standard deviations (sigma) of the elemental abundances, after correction by the dilution factor, are between 5 and 8%. Some inhomogeneities are usually found in pottery made from clay of the same clay bed. High inhomogeneities of the elements barium (Ba), calcium (Ca), potassium (K) and sodium (Na) are not unusual for pottery of the same provenance and this is why those elements, although measured with small errors, are not considered by us in determining provenance of pottery.

The Edom group does not fulfil the requirement for homogeneity. From Figure 2 it can be seen that our 'Edom group' is in fact composed of many small subgroups of only three or four samples each. The inhomogeneity of the Edom group is further expressed by the large sigma (%) for each element, as one may observe in column 5 of Table 4. However, in this study we have preferred to combine the various Edom subgroups into a regional group. The 14 abovementioned elements have a sigma < 19%. However, for further study in this field one should obtain a larger sample of all the different pottery types of the Edom group which currently comprises the following: four 'Edomite' vessels from Jordan and one from Givat Parsa, 10 'Negbite' vessels found in the Negev (see Table 2) and 10 vessels archaeologically classified as `Midianite'/'Egyptian' from smelting site 2 and Slaves Hill at Timna.

THE ORIGIN OF THE DIFFERENT ARCHAEOLOGICAL POTTERY TYPES

According to all the different data-analysis methods mentioned above, four different chemical groups of pottery were found as listed in Table 3 where all the samples are classified according to style and chemical provenance (INAA).

The entire group of 40 'Edomite' samples, of which 35 were from the Negev and five from Jordan, were divided into two chemical groups: a group of 33 and a group of five (the latter Jordanian), while two samples were chemical loners. The group of 33 showed a statistical match with the Beer Sheba waster, as also illustrated in the dendrogram (Figure 2). The second group of five Jordanian pots was locally made in Edom, since it is a statistical match with a group of five Petra wasters (see Table 4, column 6).

The 'Negbite' pottery, consisting of 27 samples from eight sites, was divided into two chemical groups of eight and 10 samples each. The remaining nine were chemical loners. The group of eight was traced to the north-west Negev, whereas the group of 10 was traced to Edom.

The `Midianite' pottery assemblage of Timna, consisting of 14 samples, divided itself into two groups (10 and two samples respectively) while the remaining two were chemical loners. The group of 10 samples shows the already known composition found in 'Edomite' as well as in 'Negbite' pottery.

`Edomite' pottery

In our previous study of Horvat Qitmit (Gunneweg and Mommsen 1990) the origin of the Edomite cult vessels (Table 2, Q1, ... Q24) was established by the chemical composition of a Hellenistic kiln waster found at Tel Beer Sheba (see Table 4, columns 1 and 2). The Beer Sheba waster was also chemically related to Iron Age II pottery archaeologically classified as

Judahite and found at Beer Sheba and Arad as shown in the same Qitmit paper. Thus, the north-east Negev group, a combined Qitmit and Qadesh Barnea group, probably also originated in the Beer Sheba region.

In the same Qitmit study it was pointed out that the Tdomite' pottery found at the Horvat Qitmit shrine had nothing in common with pottery analysed from Edomite sites in Jordan, such as Iron Age II 'Umm el-Biyarah and Tawilan. Furthermore, Nabataean Petra pottery is different in composition (Gunneweg et al. forthcoming).

At present we are able to give some more weight to the earlier results because we have ourselves now analysed `Edomite' painted as well as plain pottery from Tell el-Ghrareh and Buseirah in Jordan. Our analyses agree well with the 'Umm el-Biyarah and Tawilan (Edom) data treated in the Qitmit paper. The Jordanian `Edomite' samples have been placed in column 2 of Table 4 and this displays a composition similar to that of the Edom group listed in column 5 of Table 4. The wasters are also included in the Edom group of the dendrogram (Figure 2). One `Edomite' sherd found in Givat Parsa was traced to Edom proper.

The differences in the chemical compositions of clays and wasters from the Negev and Edom is probably due to specific differences in the geology of the regions to the west and the east of the line Sodoma-Eilat along the edge of the Syro-African rift—a Pre-Cambrian granite massif and a Nubian Cambrian sandstone formation in the east (Quennell 1956, sheet 3) as opposed to a highly calcareous sedimentary rock in the west. Clays and pottery analysed from both regions (from Oboda and Petra) yielded different chemical fingerprints (Gunneweg et al. forthcoming; 'Amr 1987).

'Negbite' pottery

Some results of the 27 `Negbite' pottery analyses were rather unexpected. Eight samples were traced to the western Negev (Table 4, column 3) because of their match with a ceramic waster from Elusa, which has been listed with its experimental errors in column 4. However, 10 additional `Negbite' vessels had their origin in Edom, including a `Negbite' cooking pot from Qadesh Barnea and four vessels from Slaves Hill at Timna. An additional `Negbite' vessel from Qadesh Barnea also matched the Edom group. Furthermore, two `Negbite' vessels found at Givat Parsa matched the composition of the western Negev.

Finally, a `Negbite' vessel (N48 from Qadesh Barnea) is of unknown origin. This vessel has a unique seal impression which consists of a rectangle with 3 Xs, topped by a crown.

`Midianite' pottery

Two painted 'Midianite' sherds (N27 and 28) from smelting site 2 at Timna show a chemical composition which is different from all pottery seen so far. This 'Midianite' pottery is chemically characterized by an unusually low calcium content ( 0.5%) and high lanthanum and thorium (75 and 25 ppm respectively), whereas cobalt is low (6.5 ppm). We have compared these data with those obtained from archaeologically defined local 'Midianite' pottery, which was obtained through the late Mrs C.-M. Bennett from Parr's survey at Qurayyah in Midian (Arabia) and analysed at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. Cluster analysis made it clear that the two sherds from Timna statistically match a mixed Timna-Qurayyah group of pottery believed to have been locally made in north-west Arabia, perhaps at Qurayyah. Qurayyah is a likely candidate because this ceramic does not analyse as Negev or Edom wares and Qurayyah is archaeologically the major site in a region which served as a corridor between Arabia and the Negev. However, additional production centres are not excluded, even at sites close to Timna.

Columns 8 and 9 show the chemical composition of this 'Midianite' pottery. Statistical comparison shows that these compositions are quite similar.

Table 5 Archaeological groups juxtaposed to chemical groups

Chemical

groups

,Veger Negev Edom Arabia Loners Total

Archaeological groups

I 'Edomite' (40 samples)

Horvat Qitmit 17 17

Qadesh Barnea 15 15

Horvat Rogem 1 1

Givat Parsa 1 1 2

Tell el-Ghrareh 3 3

Buseirah 1 1 2

II 'tiegbite' (27 samples)

Qadesh Barnea 6 1 3 10

Givat Parsa _

2 1 3

Timna Slaves Hill 4 1 5

Other sites* 5 4 9

III 'Midianite' (14 samples)

Timna site 2 2 2

Timna Slaves Hill 10 2 12

Total Negev project 33 8 25 13 81

Reference materials

Elusa waster 1 1

Petra asters= 5 5

'Umm el-Biyarah group** 1 1

Tawilan group** 1 1

Beer Sheba waster** 1 1

Beer Sheba group** 1 1

Total no. samples 35 9 32 2 13 91

* Ma'agorah. Timna site 30. Yotvata. earls Arabic Tzofar and Halugim. Gunneweg el al. forthcoming.

**Gunneweg and Mommsen 1990. II.

A second group of 'Midianite' pottery. also refered to as 'Egyptian', points again to Edom proper. This group has been grouped with other chemically similar wares in the Edom group of 25 samples. The Edom group matches five Petra wasters as well as local groups of Edomite pottery from Iron Age II 'Umm el-Biyarah and Tawilan. This is shown in columns 5-7 of Table 4.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONCLUSIONS

To determine regional contacts between peoples in the eastern Mediterranean one must obtain factual evidence of a steady or occasional trade. Usually, archaeologists are able to establish with success a link between uni-directional pottery (from supplier to consumer) and the civilization which produced it. However, claiming to have found therewith the pottery manufacturing centre is something entirely different because not many culturally-specific stylistic features correlate with geographical areas. This is needed if we are to look for regional contacts.

What emerges from this study is a typical example of how difficult it is for an archaeologist to trace artefacts to their origin by stylistic means and how natural science can help. For example, `Edomite' pottery was assumed to have been made in Edom only, whereas INAA shows north-east Negev and Jordanian sites manufacturing this ware simultaneously.

INAA suggests then that `Edomite' pottery was made in the north-east Negev and in Edom and two alternative possible explanations can be offered.

(1) `Edomite' pottery was locally made by Edomites in both regions, the Negev and Edom. Edomite script has been found on ostraca which have been shown to be of Judahite origin (Gunneweg and Mommsen 1990, 13).

(2) Judahites imitated locally in the north-east Negev a style of pottery which is also found at sites in Jordan.

Stylistically defined `Negbite' pottery thought to be local to the Negev also had its origin in the Negev and in Edom. These findings might suggest that there were no strict borders between the Negev desert and Jordan during the seventh to sixth century BC. Goods and people moved freely through the deserts. Furthermore, the Negev also imported pottery from elsewhere during Iron Age II as was shown in a provenance study of pottery found at Kuntillet 'Ajrud, a site south of Qadesh Barnea (Gunneweg et al. 1985).

The Edom district, with its strategically situated sites on the western edge of the Jordanian mountain plateau (such as Buseirah, Tawilan, 'Umm el-Biyarah and Tell el-Ghrareh), manufactured 27% of Iron Age I—Iron Age II pottery (analysed by ourselves), which implies intensive contacts between Edom and the Negev.

Early Iron Age I Timna, with its highly centralized metal-mining activities, was certainly dependent on foreign trade because no major settlements have been found near Timna which could have imported Timna's entire copper output. Although Egyptian cartouches and other finds at Timna (including the Hathor Temple itself) may point to at least an Egyptian connection there, the picture obtained from this study is much more complicated. By tracing the copper of Timna one establishes an export trade to distant countries, but this does not answer the question of who was mining and working copper at Timna. This can partly be solved by determining unidirectional trade in pottery of the people who worked there. INAA data show that 75% of all pottery analysed from Timna (Negbite', 'Midianite' and 'faience' wares) was imported from Edom proper, whereas 10% could have come from Arabia (perhaps Qurayyah).

More analyses have to be performed, but, to date, the Negev does indeed appear to have been an area of traceable multi-regional contacts. Archaeologists, however, will have to reconsider their terminology with respect to `Edomite' and `Negbite' pottery because the geographical names misrepresent the material cultural remains of the regions in question.

In the light of the results obtained by INAA we propose that the existing nomenclature of the pottery be changed for Late Bronze Age/Iron Age I as well as Iron Age II to 'desert ware' pottery, or 'tribal desert' pottery. since all the ceramics were made in the desert district east of the Sinai massif. We further propose to subdivide 'desert ware' archaeologically into 'coarse handmade ware' and 'fine ware', while the latter can be subdivided into 'plain', 'slipped', and 'painted' fine ware. Thus the title of Table I would change to 'tribal desert ware found north and east of the Sinai peninsula'.

Finally, an as yet unknown origin for a certainly Tdomite' cooking pot which has been found at Horvat Qitmit requires a further search for additional pottery manufacturing centres and this remains at present a desideratum.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the excavator of Qadesh-Barnea. Dr R. Cohen. for permitting us to sample and publish the sherds from Qadesh Barnea (tabulated as NI-26), Dr I. Beit-Arieh for the sherds from Horvat Qitmit, and for those from el-Ghrareh and Buseirah (excavated by Mr S. Hart and the late Mrs C.-M. Bennett), and Mr Y. Israeli and U. Avner of the Israel Archaeological Survey for the samples from Timna, Yotvata and small Negev sites. We also thank the archaeologists Dr B. Rothenbere and the late Mrs C.-M. Bennett, for their pottery samples submitted in 1972 to INAA at Berkeley. California.

Furthermore, thanks are due to the staff at the Nuclear Reactors Forschungszentrum Reactor Munchen at Munich and Forschungszentrum Reactor Geesthacht at Geesthacht for the neutron irradiations, and to Drs F. Asaro, H. Michel and I. Perlman for permitting us to use unpublished data from the Berkeley and Jerusalem data banks.

REFERENCES

'Amr. Khairieh.. 1987. The pottery.from Petra, Brit, Archaeol. Rep. Internat. Ser., 324.

Beit-Arieh. I.. 1989. New data on the relationship between Judah and Edom toward the end of the Iron Age, in Recent excavations in Israel: studies in Iron Age archaeology (eds. S. Gitin and W. G. Dever), Annual Am. Schools Oriental Research. 49, 125 31.

Bennett, C.-M., 1966, Fouilles d'Umm el-Biyarah: rapport preliminaire. Revue Biblique, 73, 372-403.

Bennett, C.-M., 1983. Excavations of Buseirah (Biblical Bozrah), in Midian, Moab and Edam: the history and

archaeology of Late Bron:e and Iron Age Jordan and north-west Arabia (eds. J. F. A. Sawyer and D. J. A. Clines),

9 17. J. Soc. Old Testament, Suppl. Ser., 24.

Bennett. C.-M., 1984, Excavations at Tawilan in southern Jordan, 1982. Levant, 16, 1-23.

Cohen. R., 1983, The excavations at Qadesh Barnea. 1976-1982. Qadmoniot, 61, 2-14 (in Hebrew). Dothan, M., 1965. The fortress at Qadesh Barnea. Israel Exploration J., 15, 134-51.

Franken, H. J.. 1975, Tell Deir 'Alla. in Encyclopaedia of archaeological excavations in the Holy Land (ed. M. Avi-Yonah), 321-4, Masada Press, Jerusalem (an updated summary of H. J. Franken, Excavations at Tell Deir 'Alla, 1969. Brill. Leiden).

Glueck. N.. 1935, Explorations in eastern Palestine. 4nnual Am. Schools Oriental Research, XV.

Glueck, N.. 1967. Some Edomite pottery from Tell el-Kheleifeh, Bull. Am. Schools Oriental Research, 188, 8-38. Gunneweg, J.. Perlman, I., Dothan, T. and Gitin. S., 1986. On the origin of pottery from Tel Micine-Ekron, Bull.

Am. Schools Oriental Research. 264, 3--16.

Gunneweg, J.. Perlman. I. and Meshel. Z.. 1985. The origin of the pottery of Kuntillet 'Ajrud, Israel Exploration J., 35. 270, 83.

Gunneweg. J. and Mommsen, H.. 1990. Instrumental neutron activation analysis and the origin of some cult objects and Edomite vessels from the Horvat Qitmit shrine, Archaeometry, 32, 7-18.

Gunneweg. J.. Perlman, 1. and Asaro. F., forthcoming, The origin, classification and chronology of Nabataean painted fine ware. Jahrbuch des Rinnisch-germaniches KOMI77iSSi011 des deutsche Archaeologic, 35. Hart. S.. 1988. Excavations at Ghrareh. 1986: preliminary report. Levant, 20. 89 99.

Ma-tar. E.. 1985, Edomite pottery at the end of the Iron Age. Israel Exploration J., 35, 253-69.

Mommsen, H., Kreuser, A., Weber, J. and Busch, H., 1987, Neutron activation analysis of ceramics in the X-ray energy level, Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research sect. A, 257, 451-61.

Mommsen, H., Kreuser, A. and Weber, J., 1988, A method for grouping pottery by chemical composition, Archaeometry, 30,47-57.

Oakeshott, M. F., 1978, A study of the Iron Age II pottery of east Jordan with special reference to unpublished material from Edom, unpubl. Ph.D. thesis, University of London.

Oakeshott, M. F., 1983, The Edomite pottery, in Midian, Moab and Edom: the history and archaeology of Late Bronze and Iron Age Jordan and north-west Arabia (eds. J. F. A. Sawyer and D. J. A. Clines), 53-63, J. Soc. Old Testament, Suppl. Ser., 24.

Parr, P. J., Harding, G. L. and Dayton, J. E., 1970, Preliminary survey in north-west Arabia, 1968, Bull. Inst. Archaeol. ( London), 8-9.

Parr, P. J., 1988, Pottery of the late second millennium BC from north-west Arabia and its historical implications, in Araby the Blest: studies in Arabian archaeology (ed. D. T. Potts), 73-89, Copenhagen.

Perlman, I. and Asaro, F., 1969, Pottery analysis by neutron activation, Archaeometry, 11, 21-52.

Perlman, I. and Asaro, F., 1982, Excavation of area M, in Ashdod IV (ed. M. Dothan), 'Atiqot (English ser.), 15, 75-8.

Quennell, A. M., 1956, Geological map of Jordan ( east of the Rift Valley), Ma'an, Department of Lands and Surveys of Jordan, sheet no. 3.

Rothenberg, B., 1972, Timna, London.

Rothenberg, B., 1988, The Egyptian mining temple at Timna, Institute for Archaeo-Metallurgical Studies, Institute of Archaeology, London.

Widemann, F., Perlman, I. and Asaro, F., 1975, A Lyons branch of the pottery-making firm of Ateius of Arezzo. Archaeometry, 17, 50-7.

Woolley, C. L. and Lawrence, T. E., 1915, The Wilderness of Zin, Palestine Exploration Fund Annual, 3, 62-71.

By Steve Rudd: Contact the author for comments, input or corrections.